A Dream Home Becomes a Nightmare

With their first child on the way, Stuart Crampton and his wife Violeta Roman were looking for a place to call their own.

In early 2011, they thought they had found it – a three-bedroom rowhouse on the northern fringe of Columbia Heights, the type of house that would offer the space they wanted for their growing family and a chance to move into a neighborhood that had emerged as one of D.C.'s hottest.

The 100-year-old house had been fully gutted and renovated, with new bamboo floors, a finished basement that could easily double as a play area or bedroom for visiting family, an open-concept kitchen and living room on the main floor, and a new deck off of the rear of the house.

On March 24 of that year, they signed the final paperwork for 1367 Perry Place NW. They paid $540,000.

“We signed on the dotted line after doing a home inspection, and we were real excited to start in the new house,” says Crampton, 38, who works for the federal government. “We did have a lot of optimism, we were thrilled. The whole dream house idea, that’s what we were pursuing, and happy to live in D.C.”

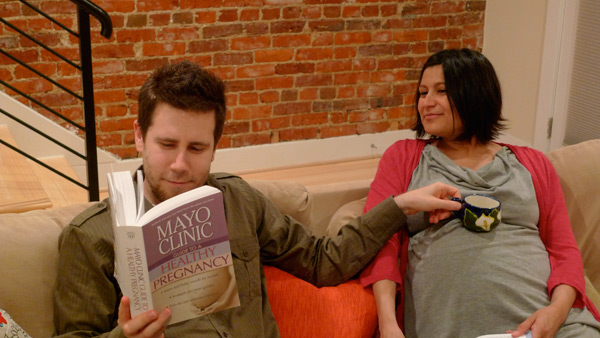

Their first few months in the house were uneventful and content. In a photograph taken in May — a month before their daughter was born — Crampton sits beside Roman in their living room. He’s reading the Mayo Clinic’s “Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy,” and jokingly has a mug propped on her pregnant belly.

But things started taking a turn in August.

“There was this bizarre earthquake that happened in the D.C. area. Out on the porch, the front porch, the casing for the porch kind of fell down partly a good three feet, kind of came detached from the roof line. We were like, ‘OK, the earthquake did some damage,’” says Crampton.

They called their insurance company, but an agent who came to inspect the damage had bad news.

“He said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, this can’t be covered.’ And we said, ‘What do you mean this can’t be covered? An earthquake just hit.’ And he said, ‘No, this isn’t from the earthquake, this is from neglect. This is all rot in here, this is all rotten wood,’” recalls Crampton. “We were sitting there scratching our heads, ‘How does our new house have rotten wood in the porch?’”

Such questions would lead them down a path of mounting problems with the house, a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against the developer and contractor responsible for it, and questions about how well D.C. has regulated the renovation of old properties during the city’s boom times.

And as they struggle to find answers, the house on Perry Place now stands empty.

A flipper’s habitat

Their story is a cautionary tale of home-buying in a hot real estate market, one in which developers quickly snatch up residential properties, renovate and sell them — often at a healthy profit. It’s also emblematic of a practice that has quickly spread in D.C. and elsewhere as real estate developers try to cash in on the city’s growth. In the nation’s capital, it’s happening too quickly for the city’s under-resourced regulatory agencies to keep up with, say some experts.

While many reputable developers and builders in D.C. call the process “renovating” or “rehabbing,” the practice of fixing up old, often dilapidated houses and reselling them at a profit is now more widely known as “flipping” — a term popularized by TV shows like HGTV’s Flip or Flop and Flipping the Block.

With home prices low during the waning years of the recession — and with D.C.’s population ticking up and its reputation as a staid government town being chipped away by the vibrancy of an emerging bar and restaurant scene — developers started purchasing single-family homes in emerging neighborhoods like Columbia Heights, the H Street NE corridor, Bloomingdale and Petworth.

“It seems like house flipping came late to Washington, D.C. It started in Phoenix and in some areas of California first, because prices hit bottom first in those areas. In D.C. there's been this window of opportunity between low-priced housing stock and really high price appreciation over the past two years,” says Nela Richardson, the chief economist at Redfin, a national real estate brokerage.

In Columbia Heights — a neighborhood that has seen an influx of white residents in recent years — home prices continued falling in the late years of the recession, offering well-capitalized buyers a chance to get in relatively cheaply. According to data from Zillow, median home sale prices in Columbia Heights fell from $420,000 in December 2008 to $381,000 a year later, and slowly started ticking up in 2010. They increased steadily from 2012 on.

Established developers say that as the real estate market recovered after the recession, new players entered the trade, many of them having little prior experience and hoping to make money quickly.

A market for ‘less than perfect’

The rowhouse at 1367 Perry Place NW was purchased for $280,000 on Aug. 31, 2010, by Real Manor ZLK, a limited-liability corporation (LLC) controlled by Jay Gulati, a Maryland-based developer.

Gulati is the son of Ripudaman Gulati, who is also involved in real estate in D.C. He has twice been sued over housing conditions at two of the low-income residential properties he owned in the city, and in 2000 pleaded guilty to improperly disposing of 110 bags of asbestos during the renovation of one of his properties.

Jay Gulati’s LLC also purchased more than a dozen homes in Columbia Heights and Petworth — many located only blocks from one another — and quickly flipped them, selling them for prices that regularly exceeded $500,000. Gulati also used a number of other LLCs to purchase homes throughout the city. All his LLCs are registered at his $2 million, 5,000-square-foot home in Potomac, a tony suburb in Montgomery County.

In 2013, a Redfin analysis found that the average gain in D.C. in the difference between the purchase and sales price from a flipped home was $104,100. While some cities in California — where there was a more significant drop in home values during the recession — posted higher average gains, two D.C. neighborhoods — Petworth and Brookland — led the nation in gains, at $312,400 and $271,900, respectively.

The profit potential on sales of flipped homes in many emerging D.C. neighborhoods has attracted investors and developers from outside the city, like Gulati. That, says one local developer, can carry risks for homebuyers.

“The District has had a strong housing market, and whenever there’s a real strength in the housing market or whenever there’s a great amount of demand for properties, that means that properties that maybe don’t have everything done appropriately move and sell. It allows for work that’s less than perfect to sometimes slide through the cracks,” says Bo Menkiti, owner of the Brookland-based Menkiti Group, which sells and redevelops property in the region.

That can mean homes where aesthetics trump quality, where new drywall and hardwood floors mask serious flaws. And while it can be hard to judge just how extensive the problem is — some developers say it’s only a small number of players — one longtime builder says that there are plenty of examples of poorly flipped homes.

“What I do see is substantial,” says Ethan Landis, a builder and member of the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs’ Construction Code Coordinating Board. The board works on updates to the city’s building code, and Landis' own firm, Landis Architects/Builders, has uncovered — and fixed — problems at flipped homes.

Even worse, Landis says, is that unless problems are caught before a sale is finalized, they can dog the new owners for years to come. “I can say that when someone buys a poorly renovated home," he says, "they’re in for a world of hurt.”

A toxic investment

After Crampton and Roman discovered the rot in their porch, the problems quickly added up for the couple, who welcomed a daughter, Ama, to the family in June 2011.

Their basement periodically flooded. They attributed it to an incorrectly graded area behind the house — where the new deck had been built — that caused water to pool by the basement door during storms.

The house was also cold during the winter months, so much so that they had to move their daughter back into their master bedroom because she kept getting sick.

“We had some insulation people come in, and they confirmed that behind the shiny new drywall was empty as an eggshell, no insulation behind the drywall, none in the ceilings, none anywhere. So that’s what was making the house so cold, that and the defective HVAC system,” he says. Insulation is required under the city's building code.

They also suffered another flood in the basement, this one caused by pipe they say was blocked by construction debris. Sewage backed up into the basement and onto the carpet.

While addressing that issue, they discovered what Crampton says was the most disconcerting problem with the house.

“When they removed the carpeting to get rid of all the sewage-soaked carpeting, there were some funny looking tiles on the floor of the basement. Somebody had mentioned to us, ‘Those tiles look a little odd, you probably need to get those tested, especially with everything else you’re finding in your house,’” he remembers.

“So we had an environmental hygienist come in and test the tiles, these old tiles, and sure enough, there were asbestos-containing materials. And it’s not just that they contained asbestos, the tiles were, they looked like half of the room of tiles had been jack-hammered and there were pockmarks, so it looked like they had been disturbed and then concealed,” he says.

They also discovered that the basement bedroom and one of the two bedrooms on the second floor did not have the needed egress windows to qualify as bedrooms according to city regulations, meaning that if Crampton and Roman were to resell the house, they would have to list it as a one-bedroom property.

All of these problems emerged even though the couple had hired a home inspector to look at the property before they bought it. While the inspector did identify a number of small issues that Crampton and Roman asked the seller to correct, there was little that could be done to find the larger flaws — many of which were concealed by drywall and carpeting.

Trying to fix those problems only created more. When Crampton hired a company to insulate the house, the material it used didn’t cure properly and leached noxious gases.

Fearing for their health — and Ama’s — the couple moved out of the house at the end of 2013.

“At the beginning, we were, to be honest, in denial, maybe me especially. I don’t think I wanted to admit to myself that we got taken, that we bought a lemon," Crampton says. "You want to believe that your new house is here to stay, that this was a good investment. It was not."

A multimillion-dollar lawsuit

In March 2014, the couple filed a lawsuit in D.C. Superior Court, alleging that Gulati, seller Sunil Chhabra (who is Gulati’s brother-in-law, and a realtor with Maryland-based A-K Real Estate) and general contractor Michael Crisci perpetrated “fraud and wrongdoing” when they flipped the house. They’ve asked a judge to award them more than $5 million in compensatory damages and $8.5 million in punitive damages.

Gulati, Chhabra and Crisci declined to comment for this story, but lawyers for each responded to emails from WAMU 88.5 to say they all deny the accusations leveled by Crampton and Roman.

The lawsuit claims that Gulati, Chhabra and Crisci engaged in illegal construction on the house, obtaining permits for some basic work, no permits for other work, and in many cases exceeding the scope of the permits they were granted.

Load-bearing walls and beams were removed without the proper permits, the couple alleges, an unpermitted deck was built, required inspections were skirted, and problems that sellers legally have to disclose — such as the age of the roof and presence of lead in the house — were simply not shared with the couple.

Additionally, they say, Crisci, who served as the general contractor for the house, was not licensed to work in the city at the time.

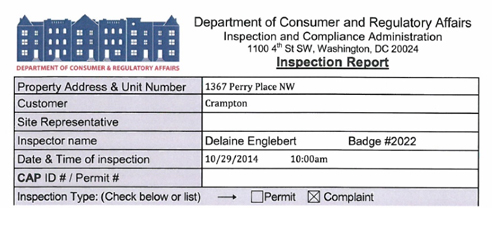

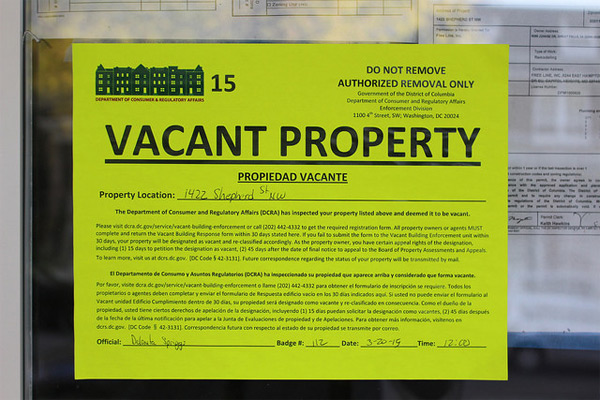

An October 2014 inspection of the house by Delaine Englebert, an illegal-construction inspector at DCRA, confirmed that there were numerous problems. She catalogued three dozen violations, including unpermitted work, unfinished inspections, insufficient fire-blocking throughout the house, new structural beams that are not properly supported, a deck not correctly attached to the home, a failure to insulate the house, and more.

Earlier this year, the couple hired Ethan Landis, the builder, to assess how much it would cost to bring the house up to code.

“We could see there was no insulation put in, we could see that structural members had been removed — walls — that shouldn't have been, we could see that there were all kinds of code violations that normally are concealed and the untrained eye wouldn't see them,” he says.

To make the house livable again, Landis estimated the couple would have to spend $407,000 to correct all the existing deficiencies and code violations.

A real estate expert the couple hired quantified the financial impact in another filing: He said that while the house without defects could be worth up to $573,000 on the open market today, all of the problems had dropped its value to $220,934 – less than what Gulati had purchased it for.

Costs above everything?

In court filings responding to the lawsuit, Gulati and Chhabra’s attorneys say they were not involved in day-to-day decisions on construction in the house, nor were aware of any of the problems that have since been found.

“If the Plaintiffs’ allegations are correct,” wrote Gulati’s lawyer in a September filing, “their damages were caused by the negligent or intentional acts of others.”

That would be Crisci, as well as a permit expediter who Gulati and Chhabra say was hired to pull the proper permits for the work.

For his part, Crisci has denied that he was unlicensed, though DCRA says it has no record of him or his company being licensed to work in the city at the time. He also accuses a number of subcontractors who worked on the house for the problems that resulted. In one filing, Crisci’s attorney says the Virginia-based contractor “did not supervise or oversee the quality of work on the project.” He also says that Crisci “did not inquire into the subcontractors’ licensing, certification, etc.”

But whether or not Gulati, Chhabra and Crisci were aware of the corners that were cut, the problems that later emerged were not limited to Crampton and Roman’s house. The owners of three nearby rowhouses also flipped by Gulati around the same time say they discovered similar problems shortly after buying.

“The developer looks like he cut corners in our house, and did things that were aesthetically pleasing or quick,” says one of the owners, who paid $620,000 for a house that Gulati had originally purchased for $350,000. She asked that she not be identified by name due to concerns with the impact that the revelations could have on her home’s value.

The HVAC system in her home was not properly installed and needed additional work to be made fully functional, the house was not insulated and a gas meter had been illegally moved during construction, leading Washington Gas to turn off gas to the house for three months during the fall and winter.

Another owner also found her house not to be insulated and problems with some plumbing work, and a third says the HVAC had not been properly installed. She also says that she’s had to pay to have the windows of her basement bedroom changed out so they meet the city’s standards for what qualifies as a bedroom, and like Crampton and Roman, she suspects her rear deck was installed without permits.

In a December 2010 email exchange between Gulati, Chhabra and Crisci that was made available as part of the lawsuit’s discovery process, the three discussed needed repair work on a chimney on another Columbia Heights rowhouse they were flipping. “We can just give it a go. If it comes loose a month from now it can be on the homeowner,” wrote Crisci. “[Y]eahhhh lets (sic) just do our best,” responded Chhabra.

Not all of Gulati’s homes showed such problems, though. The owners of two homes in 16th Street Heights he flipped and sold say they have not had any of the issues Crampton and Roman did since purchasing.

Landis and others say that the root of the problems at the Columbia Heights homes was likely a combination of fast turnaround — Gulati gave Crisci two months to completely gut and renovate the home that was sold to Crampton and Roman — and a desire to cut down on costs.

“Ultimately, one has to assume the motivation is money, that these people know they're selling this home, they hope they'll never be called back and never see the home again, so they don't have any personal or professional integrity to say that, 'This home represents my brand or what my company is committed to building,’” says Landis, who has been working in the region for 25 years.

An October 2010 email from Gulati to Chhabra released through discovery highlights how keeping costs down was an important factor for Gulati.

“So I think the right attitude should not be make the homes perfect and we will get the premium, It should be, let’s spend as little as necessary to get to our price target, we should save what we can save to reduce our expenses. We can’t be worried about losing a few contracts because home inspectors scare off our buyers. Sometimes we are guilty of overreacting to things… We are not doing new construction… we are doing renovations… which means you can save things and work with what you have,” he wrote.

In March, after Crampton and Roman had put an offer on the house, Chhabra expressed frustration with some of the fixes that the couple had asked to be made before closing. “Buyers are getting more annoying by the day,” he wrote to Crisci.

‘Basically a Wild West’

It’s been more than a year since Crampton and Roman filed their lawsuit, and they’re still working their way through mediation and settlement talks.

They’ve been out of their house for 18 months. It is now almost completely gutted, a product of the repeated inspections and assessments they’ve had done and a belief that almost none of the work done by Crisci and the subcontractors is worth keeping.

“You pull together your life savings, you borrow, you invest in your future, in your home, and you want things to be lasting. It’s going to be the nest you raise your kids in and all that," Crampton says. "So then when you find out the people who sold you this house, this nest, did it in a way where they misrepresented and omitted material facts about the safety of the house, I felt, you know, angry, sad and worried about the health aspects."

He has found focus in digging up information on what went wrong — and how it went wrong. Part of the blame, says Crampton, is that DCRA isn’t equipped to enforce the city’s strict building codes.

“What we’ve ended up with in D.C. because of the home renovation boom is basically a Wild West, and you have a lot of flippers, home renovators, developers who, although there are plenty of good ones out there and plenty of them who do rejuvenate the communities and the neighborhoods, there are way too many who are out there just to make a profit without regard to the laws governing safety and health,” he says.

As the legal process drags on, Gulati, Chhabra and Crisci have continued working on different properties.

Crisci has a new contracting company, which is properly licensed with DCRA. And he’s not only working on homes that other developers buy to flip, but he is also purchasing his own D.C. homes to flip and resell.

Gulati runs Westend Development, which he uses to purchase homes and resell them to other developers and builders. People with knowledge of his work say he has largely stopped renovating homes himself. In one example, Gulati purchased a rowhouse on W Street NW in 2013 for $400,000 and resold it a year later to another builder for $875,000. The house is being converted into a three-unit condo building.

Chhabra continues working with Gulati, and also recently established an organization — Pro D.C.’s Future — that he used to lobby against a proposal that would limit the height of pop-up developments in certain residential neighborhoods. (The D.C. Zoning Commission approved the proposal in March.)

They may soon have to answer questions from city regulators about Crampton and Roman’s home, though — DCRA says it is investigating the numerous code violations and the role that Gulati, Chhabra and Crisci may have had in them.

And they aren’t the only developers that have recently come under scrutiny from city regulators. In Part 2, we've got the story of a flipper whose business has caught the attention of D.C.'s attorney general. And in Part 3, we'll examine the D.C. government's ability to keep pace with the industry.

Part 2: A Great Fall

For The Developer From Great Falls, A Great Fall

Update, May 7: D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine has filed a complaint in D.C. Superior Court against Insun Hofgard over her flipping of 15 residential properties in D.C. since 2013. Read the story.

When Trina Dolenz first toured the renovated rowhouse on 2nd Street NE in Eckington last year, she was quickly drawn to it.

“It was absolutely wow. [The developer] had used top-quality washing machine, fridge, appliances, beautifully done, and exactly what I would have done personally. High-quality specs visually. It looked like it was a really, really good job,” she says.

Dolenz, a couples therapist who was looking to move to D.C. from Los Angeles to be closer to her children, decided to put an offer on the house. But as closing approached and she had it inspected, the initial visual appeal gave way to a host of problems.

“It was skylights, things to do with the HVAC system, electrical, heating, plumbing, just things that were not according to code. They were things that I wouldn’t have caught personally,” she says.

“There were obvious things, things that, you know, a light upside down, the flooring was all done incorrectly, there were leaks, there were going to be potential leaks in the ceiling, joints on the roofing, which of course I couldn’t have seen, sort of sloppy work,” she adds.

In public documents, a clear picture emerges: In one way or another, she was in over her head.

As Dolenz and her inspector pointed out the problems, the developer, Insun Hofgard, would send contractors over to address them. After a few rounds of fixes, Dolenz felt comfortable enough to close on the sale, paying $630,000 in March 2014. Hofgard originally had bought it less than a year prior for $280,000.

After the sale, more problems popped up for Dolenz. First it was the water heater — it couldn’t properly serve all three bathrooms. Then the HVAC system — it couldn’t adequately heat or cool the house. Dolenz called Hofgard; the developer was at first difficult to reach, but later agreed to upgrade the HVAC system.

A year into living in the house, Dolenz says she’s happy with the purchase, despite continuing evidence of what she says is low-quality work done before it was flipped.

She doesn’t have much good to say about Hofgard, though.

“I don’t know this for a fact, but I fantasize that she was sort of doing this for fun. She was a sort of rich housewife having fun being a developer, and it was a sort of project for her," Dolenz says. "So I don’t think she really knew what she was doing, but found the whole thing exciting and fun, and she was making money, and she was hiring terrible people and not really realizing it.”

Hofgard offered limited responses to WAMU 88.5's questions about her development projects, but in public documents, a clear picture emerges: In one way or another, she was in over her head.

Expanding market, bigger risks

Dolenz didn’t know it at the time, but she wasn’t alone in her experiences with Hofgard. In recent years, the developer purchased, renovated and resold dozens of homes, sparking complaints and lawsuits from homebuyers who, like Dolenz, found significant issues hidden below new flooring and behind new drywall.

Hofgard is hardly the only property flipper to draw such attention in D.C., but her impact is larger than most — and it speaks to the rapid changes in the residential housing market since the end of the recession.

The promise of quick riches from renovated properties in revitalizing neighborhoods has attracted many new players. Those flippers have created additional choices for buyers in a city where established, big-name developers handle a lot of the inventory, but the newcomers can have far less experience in navigating D.C.'s regulations and working with the city's older housing stock.

And when things go wrong, the effects not only hit the customer, but also the city's legal system, too. In Hofgard's case, the number of affected homeowners and properties is large enough to have attracted the attention of D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine, who was elected in 2014 after campaigning to strengthen enforcement of the city’s consumer protection laws.

Irresistible opportunities

According to city records, Hofgard started purchasing and flipping residences in mid-2010. She had worked on commercial properties in Colorado and California before, say people with knowledge of her work, but the lure of D.C.’s residential market prompted a change in interests.

Her first three projects involved converting rowhouses in Bloomingdale and Eckington — both neighborhoods on the upswing at the time — into multi-unit condominium buildings. She worked with a partner, developer Abhijit Dutta, on the projects, and Hofgard was responsible providing capital and financing for the renovations.

She named all three projects after herself — “The Insun,” followed by the address of the property — and they proved to be profitable: A house on Quincy Street NE was purchased for $305,000 in 2010, and two years later the two new condo units sold for $505,000 and $455,000, respectively.

Hofgard, 53, later set off on her own and her flipping picked up steam in 2012, as she purchased, fixed up and resold more than a dozen properties. She showed a certain preference for Bloomingdale and Eckington, densely populated areas with long blocks of rowhouses. She also made purchases in nearby Columbia Heights. Over the course of a year from August 2012 to July 2013, she acquired at least 16 properties.

She bought some of the properties with her husband, Jefferson Hofgard, a former senior official in the White House under President Bill Clinton and a current vice president at Boeing. And like many developers, she purchased and sold other homes using a number of limited-liability corporations (LLCs) registered at their $1.7 million, 6,000 square-foot home in Great Falls, Virginia, a bucolic suburb northwest of D.C.

The number of properties she purchased caught some established developers by surprise, but no one was more surprised than some of the residents who bought homes she had flipped.

Scrutiny intensifies

In April 2013, Jennifer Headley paid $599,000 for a rowhouse on V Street NE in Eckington. Hofgard had bought the house a year earlier at a foreclosure sale for $280,000 and flipped it.

“Total renovation… No detail spared,” boasted the listing for the house, which was built in 1910. “House features open floor plan, exposed brick wall, bamboo flooring, gas fireplace, gourmet kitchen. 3 bedrooms, 3.5 baths, family room, wet bar!”

But in a lawsuit filed against Hofgard in July 2014, Headley said that many details were in fact spared.

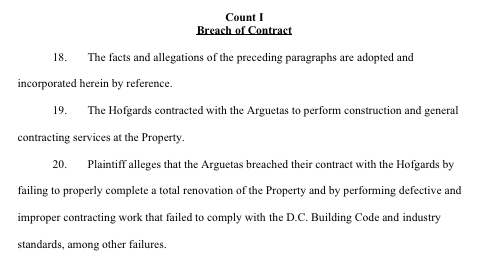

Load-bearing walls and beams were removed without permit and never replaced, threatening the home’s structural integrity. The roof — which Hofgard advertised as new — had been improperly patched, the wood in the porch had been painted over to conceal rot, a leak in the basement was compromising the home’s foundation, and there were installation problems with gas lines and the HVAC system. All of the work, Headley claims, was done by unlicensed contractors hired by the Hofgards.

Headley, who declined to comment for this story due to ongoing settlement talks, says in the lawsuit that the problems forced her to take out a second mortgage worth $75,000 to pay for repairs and cost her thousands of dollars in attorney’s fees, as well as missed work days.

Her lawsuit accused Hofgard and her husband of violating the city’s consumer protection laws, intentionally misrepresenting the renovations on the house, breach of contract and unjust enrichment. Headley asked for over $1 million in compensatory and punitive damages from the Hofgards.

In late April, Headley and the Hofgards agreed to the outlines of a settlement. The details were not disclosed to WAMU 88.5.

‘Bought a nightmare’

In December 2013, Patricia Simon and her husband Timothy Snowhite bought one of two condo units in a Columbia Heights rowhouse Hofgard had originally purchased for $525,000 in May 2012. The couple paid $764,980 for the 1,280-square-foot, three-bedroom, three-bathroom unit that had been fully renovated. (The second unit was sold in February 2014 for $670,000.)

But as with Headley’s home, the quality of the work didn’t extend past the aesthetics. Though neither Simon nor Snowhite wanted to comment for this story, their lawyer, Mark Moskowitz, says that the couple suffered at the hands of Hofgard.

“My clients sought to buy a home where they could have a place to live in the city, have all the amenities and conveniences of living in what was advertised as new construction. And unfortunately, they bought a nightmare,” he says.

Ethan Landis, a builder with 25 years of experience in the region, was brought in to review the work and assess what it would take to correct it. He identified dozens of violations that he estimated would cost more than $200,000 to correct.

“In their home, they had to replace the roof, they had to redo a roof deck, they had other leaks coming into the house, they had a poorly installed HVAC system, they had under-structured floor systems that had way too much shake in them, they had non-separation of fire barrier between the lower and upper unit, they had light fixtures that were installed that allowed air and ultimately a fire to go around the light fixtures very quickly which doesn’t meet the building code, they had plumbing issues, they had a multitude of issues that we found with a fairly cursory survey of their home,” he says, rattling off the problems he found.

Beyond that, Hofgard had not obtained the certificate of occupancy required before such projects can be completed and sold.

Sizing up the contractors

In both written responses to questions posed by WAMU 88.5 and filings in response to Headley’s lawsuit, Hofgard says that the blame for the problems at those homes lies with the contractors she hired to do the work.

“I relied and trusted my contractors whom I paid fairly to renovate and construct according to approved sets of plans and permits fully approved by [the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs],” she wrote in an email.

After Headley filed her lawsuit, the Hofgards sued those contractors — Virginia-based Edwin Aguirre Argueta and Abilio Argueta. In Sept. 2014, the Hofgards sued the Arguetas, claiming that any responsibility and liability for Headley’s claims was on the contractors. In December, Edwin Aguirre Argueta responded with his own court filing, saying that the Hofgards assumed any and all risks of the allegedly negligent work. (According to court documents, Abilio Argueta has not been found and was not served the original lawsuit.)

A lawyer for Edwin Aguirre Argueta did not respond to a request for comment on the claims. But it isn’t the first time he and his contracting company have been in court. In August 2013, two residents who had purchased a renovated home in Bloomingdale from the Arguetas sued for what they said was shoddy work.

Additionally, in August 2012, a tenant of a home next to one that had been purchased by Hofgard and was being renovated by the Arguetas sued, claiming that they did damage to the adjacent home during construction.

People who have worked with Hofgard say that it is possible that the Arguetas may have been the source of the problems.

“I had heard that her work product was good. She’s had different general contractors, so I don’t know which general contractor was good and if she any that were bad, but I had heard that her work product was good, that there were quality materials, that things were done right,” says Ben Soto, a settlement attorney who worked with Hofgard on the sale of various of her properties. He also filed the paperwork to create the LLCs she used to purchase and sell the homes.

Trina Dolenz met the Arguetas when they came to her home to complete repairs she had requested of Hofgard, and she says she was not impressed with their work.

“The guy who was her head contractor, and he went on to do the next project up the road, he was an absolute idiot. And when it came to me asking them to finish the small jobs, I then after awhile said, ‘I’m not having you in the house,’” she says.

Other developers say that overseeing contractors is an important role for a home renovator and seller has to play.

“We’re very close,” says Mark Rengel, vice-president for the Menkiti Group, of his relationship with the contractors that renovate homes. “That daily visit from our project manager, he sees what’s going on, so if something doesn’t smell right, it usually comes up very quickly in the process.”

In one written response provided by Hofgard, she says she responded by both firing contractors and offering to pay for any repairs.

“I dismissed those contractors who had performed non-compliant work once it was made aware to me, and in every single step I offered to fix the problem directly at my costs,” she says.

Soto concedes that the day-to-day management may have been a problem for Hofgard. “As a settlement attorney, I don’t play a role in the construction management of it at all, but it’s obvious, with litigation and everything circulating, that she’s had some issues,” he says.

But he insists that not all of her home sales ended in acrimony. “I’ve conducted closings for her buyers where they were happy.”

Promises broken?

But by late 2014, the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs — which issues permits for construction and enforces the city’s building code — had started catching up to Hofgard.

On Nov. 26, DCRA and Hofgard signed a settlement agreement, a legal document in which Hofgard admitted to a number of construction-related infractions on four properties in Bloomingdale and Eckington she had purchased and had started flipping.

Under the agreement, Hofgard would pay $32,500 in fines, and in exchange DCRA would remove stop-work orders that had been placed on the properties. She also pledged not to sell any other properties she owned “prior to receiving final inspection approvals, required permits, and any Certificate of Occupancy.”

The message was clear: Any future sales of Hofgard’s flipped properties had to follow the letter of the law, with all appropriate permits and inspections. Her signed pledge, say sources with knowledge of her case, didn’t even last a day.

Beyond paperwork

A YouTube video of the house at 238 Madison Street NW in Manor Park, which Brian Jacobson and his husband purchased. They later found it to have numerous problems.

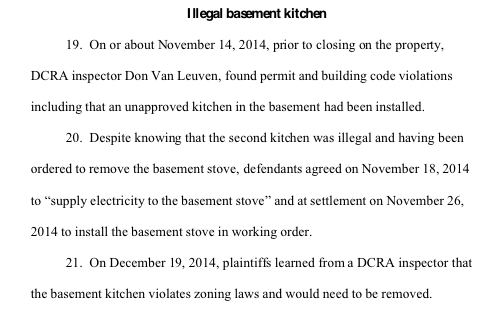

That same afternoon, Hofgard signed off on the sale of the house at 238 Madison Street NW to Brian Jacobson and Branko Jovanovic for $640,000. She had purchased the Manor Park rowhouse a year earlier for $360,000. On the day they signed the contract, it was amended to allow for “final inspection and approval” by DCRA by Dec. 11, after which they could move in.

Unbeknownst to the couple, the renovations were completed without the proper permits. Additionally, outstanding violations remained unaddressed and none of the required inspections were completed or approved.

On Dec. 19, a week after the couple had moved into the house, a DCRA inspector visited the home. Multiple sources say that the inspector was unaware that the house was occupied. She issued a stop-work order on the property for the work that was completed without permits and the inspections that had not occurred.

Last month, DCRA sent the Hofgards a Notice of Infraction identifying two-dozen code violations, from a failure to obtain a building permit to gas lines that were not properly installed. The fines for the combined violations add up to $15,000.

On April 29, Jacobson and Jovanovic sued Hofgard in D.C. Superior Court, asking a jury for $1 million in damages, along with punitive damages and attorney’s fees.

The lawsuit outlines a number of deficiencies in the house, including an illegal kitchen in the basement, poorly installed insulation that led to a burst pipe and flooding in their basement in February, plumbing problems, structural defects, and lighting fixtures that posed fire hazards.

“We were like, ‘OK, this a little irritating. It’s new construction, I suppose these things happen,’” says Jacobson of their initial response to the flaws they found. “When the inspection happened, it really turned to anger. The feeling that there are too many things wrong for this to be a coincidence.”

The lawsuit claims that the work on the house had be completed by the Arguetas, the same contractors who had worked on Jennifer Headley’s home.

A warning to homeowners

Earlier this year, Hofgard sold one more property: An Eckington rowhouse that, like others before it, had been renovated and divided into two condo units.

But unlike her past sales, this one occurred under additional scrutiny from the city, and was only finalized after she obtained the necessary certificates of occupancy and had rebuilt a rear deck she had added but the city said was too large for the lot.

The owner of one of the properties, who asked not to be identified, said he had found no further problems with the property, but that he had received a letter from DCRA informing him that his new condo may be inspected for any evidence of defects.

The letter, which came from Hamilton Kuralt, the manager of DCRA’s Office of Consumer Protection, read: “A recent review of agency records revealed potential issues with the pre-sale renovation of your property. It appears that the construction may not have been in full compliance District laws pertaining to construction, permitting, and construction inspections.”

That same letter was sent to 17 other homeowners who had purchased from Hofgard.

The Eckington property's owner also was contacted by the D.C. Attorney General’s office, which confirmed to WAMU 88.5 that it is investigating Hofgard and the many properties she flipped and sold.

As the city continues investigating Hofgard, a number of her other properties remain unfinished and unsold, stalled by stop-work orders issued by DCRA.

Since September, the agency stopped work on eight, most often for construction that exceeded the scope of the permits that had been issued. Some of the properties also have been declared vacant, a designation that substantially increases the property tax rate.

And there have been other problems. In August, the fire department had to be called to a Hofgard property on Adams Street NW in Bloomingdale because of a partial roof collapse that occurred during work to add a story to the home. That home, set to become two condo units, remains unfinished.

In her written responses to WAMU 88.5, Hofgard insists that she tried to correct the mistakes made by her contractors.

“I offered all of my previous purchasers who have had issues, to address and repair any deficiencies to their full satisfaction,” she writes.

But she also insinuates that regardless of all the issues they may have faced, the homeowners may end up benefiting from the experience.

“You also need to keep in mind that many of these homeowners who have filed complaints against me for monetary gain has not only benefited from settlement amounts, but also a great appreciation in their home values over the last two years,” she says.

But on Madison Street, Jacobson says he doesn’t feel that way. He guesses that he faces a long road before a resolution with Hofgard over the repairs that need to be made to his home. But even if they are made, he says he’s not sure he will want to stay in the house afterwards.

“We’ve just been so burned by this experience,” he says. “We’re looking at another six months of remodeling. After that six months, I don’t know if I really want to be in that house anymore.”

Part 1: A Dream Home Becomes a Nightmare Part 3: Can Regulators Keep Up?

As Development Spreads Across D.C.’s Neighborhoods, Can Regulators Keep Up?

On a Saturday afternoon in late April, a group of about a dozen Petworth residents walked from one property to another in the Northwest D.C. neighborhood, pointing at rowhouses in various states of demolition or construction.

The rear wall of a home on Varnum Street had been removed, exposing the gutted three-floor interior of what a developer hopes to turn into a four-unit condo building. Over on Randolph Street, another home had been fully demolished; nothing was left standing but its facade. On Quincy Street, a faded stop-work order adorned the front of another rowhouse halfway through the addition of a third story.

The residents complained that many of the projects lacked proper permits, that developers had started substantial work without notifying adjacent homeowners, and that damage was sometimes done to neighboring homes. It’s a story told by residents of many neighborhoods where developers are buying, renovating and reselling residential properties.

The group in Petworth was joined by D.C. Council member Vincent Orange (D-At Large), who leads the committee that oversees the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs, the agency charged with both issuing building permits and enforcing the city’s building code.

But to hear the residents tell it, DCRA isn’t doing either very well.

They said that as developers snatched up residential properties throughout Petworth — which real estate broker Redfin has ranked as one of the nation’s most lucrative destinations for home flipping — they would often engage in illegal construction when renovating the homes, whether for single-family use or as multi-unit buildings.

The residents complained to Orange that they often had to fight for themselves, whether the developers were working beyond the scope of permits they were granted or were starting certain work without properly notifying people in neighboring homes. Those comments were hardly new.

“Most of my time is spent addressing complaints from residents about developers who do not follow the proper rules and regulations and the lack of oversight on the part of DCRA,” wrote Kathleen Crowley, the head of an Advisory Neighborhood Commission in the area, in a letter to legislators in March. “Let me be clear, I am not talking about simple matters of permit creep but rather egregious examples of developers going well beyond what the permits allow."

The lack of oversight and enforcement by DCRA has been a recurring theme during the city’s real estate booms. As more construction happens — whether homes being flipped, expanded or converted into condo units — the agency is strained with issuing permits in a timely way and then policing the builders to ensure they are doing only the permitted work.

Unscrupulous developers, say some residents, exploit weaknesses in enforcement and view fines as the cost of doing business to quickly flip homes. In the process, they can do damage to adjacent properties. Or as with Stuart Crampton, who purchased a flipped Columbia Heights rowhouse in 2011 that he says was renovated illegally, the construction does not meet the standards set out by the building code.

After Crampton filed a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against the developer of his home, DCRA took notice of the case and sent an inspector to check the property in October 2014. The resulting inspection report catalogued 36 code violations.

But for Crampton, it was too little, too late.

“After a while, you have to wonder, someone’s asleep at the wheel at DCRA, or it’s willful ignorance or it’s complicity,” he says. “I don’t know exactly. Maybe it’s a combination of all those things, but it’s disheartening.”

Soft consequences

While most developers, real estate experts and legislators say that DCRA has improved by leaps and bounds over the last decade, the agency is still dogged by complaints on both ends of the development process.

Developers say that anything above the level of a cursory permit for interior work in D.C. can take months to review and approve, leaving projects stalled and chipping away at the carefully calibrated financial plans that firms have for properties.

As a result, the companies that try to do things by-the-book find themselves waiting six months or more for permits. Developers who are willing to cut corners, meanwhile, have a big incentive to apply for only basic documents — such as a permit for interior work only — and then exceed their scope as they work.

“The permitting process is complicated, and I understand why it should take three, four, five weeks for a complicated residential project,” says Ethan Landis, a builder who also sits on DCRA’s Construction Code Coordinating Board, which reviews and updates the city’s building code.

“The longer it takes to get a building permit, the more likely a developer holding this property wants to skirt the rules and get into construction,” he says.

DCRA's inspectors can check construction sites for permits and issue stop-work orders if there are no permits or the work being done does not match what was permitted. But the agency’s three dedicated illegal-construction inspectors — there are four positions, though one is currently vacant — are not enough to police all the development happening in D.C.

“Three is not really enough for a city this size, not with this many neighborhoods that are emerging and developing and becoming restored and nice places to live,” says Cindy Verbeek, who runs the D.C. chapter of the Institute for Building Technology and Safety (IBTS). “As much construction as we know is going on, three people can’t really handle it in a day.”

Critics also say the fines for violations — which can range from a few hundred dollars to $2,000 per offense — are too low, and that many developers see them as a drop in the bucket of projects that can net them tens of thousands of dollars in profit, if not more.

“It’s worth the price of the fine, because they can pay a $2,000 fine for illegal construction, or $11,000, but in the end they’re saving $80,000, perhaps even more, because they don’t have to wait for permits to be processed, because they don’t have to pay for licensed labor, because they don’t have licenses to operate in D.C.,” says Crampton.

Additionally, statistics from DCRA show that the agency has only collected half the value of the fines is assessed for illegal construction over the last three years. In 2012, there were 631 Notices of Infraction (NOIs) issued worth $2.2 million in fines, though only $1 million was collected. In 2013, it was 430 NOIs worth $1.5 million, with only $700,000 collected. And last year 413 NOIs worth $1.4 million only resulted in $510,000 being collected.

Finding what works

Melinda Bolling, the agency’s interim director, says that she is focused on illegal construction, especially as development spreads to residential properties beyond the hottest neighborhoods.

The targets are “individuals who are investing in real estate and redeveloping them for resale and haven’t either understood the laws here in the District or are purposely trying to skirt the laws in the District,” says Bolling, who has been at DCRA since 2007, rising from attorney to general counsel and taking her current job earlier this year.

Bolling says the agency is working to streamline its permitting process by allowing developers and builders to submit plans electronically, which would allow for multiple people to review them at the same time. With the new system, permit review times will decrease, she says. And she disagrees with the idea that she doesn't have enough inspectors. The agency can redeploy other inspectors to focus on illegal construction, she says.

Bolling also says that fines aren't its most effective punishment. “I think the biggest tool that we have in our arsenal is a stop-work order, because when we stop you, that’s costing you thousands of dollars in construction time,” she says.

“We’re not really trying to get fines. We’re trying to get compliance. I think homeowners and the consumers don’t care if we get the fines. They want to make sure that the home they’re buying complies and is going to be habitable for them for years to come,” she adds.

Last year, DCRA issued 551 stop-work orders, up from 2013, when 506 were issued. But it’s a drop from the three years before that. In 2010, there were 742 stop-work orders, in 2011 there were 616 and in 2012 there were 693.

Overall, Bolling says that she’s pushing the agency to sharpen the various tools it has to address illegal construction.

“We’re looking to do more quality control and to come up with ways so that the consumer doesn’t have to fear purchasing shoddy construction,” she says.

Insiders vs. outsiders

One area where Bolling is making changes to is DCRA’s third-party inspection program, an initiative within the agency that draws passionate arguments from supporters and from critics.

Under the program, developers and builders can opt to have required post-construction inspections done by one of 65 third-party firms. Advocates of the program say that it provides a valuable — and speedier — alternative to DCRA’s in-house inspectors.

“DCRA does not have the staff to handle all these inspections. And, frankly, the reason there is a third-party program at all is because DCRA, it will take them two to three days to get out there, where most third-party agencies will be there the next day. It speeds up the process,” says Verbeek, whose firm is in the third-party inspection program.

Ethan Landis, the builder, agrees. “I personally think the third-party inspection program is a huge benefit to many parts of the industry, he says.

Mark Moskowitz disagrees. He’s a real estate attorney who represents a couple that purchased a flipped Columbia Heights home from Insun Hofgard, the Virginia developer we reported on in Part 2 of this series. According to him, the program is DCRA’s biggest Achilles' heel when it comes to enforcing the building code and protecting consumers.

“When you go ahead and outsource something as important as inspections to determine the safety and habitability of residential property, and you outsource that to people who are solely beholden for their compensation to the developers that are paying them, you are allowing the fox to guard the chicken house,” he says.

In Hofgard’s case, DCRA seemed to come to this very conclusion. After finding multiple violations at properties she was renovating, DCRA had Hofgard sign an arrangement under which she paid fines and agreed not to sell any other properties that had code violations. She also promised to get all pre-sale inspections -- but the agreement specified they would have to be conducted by DCRA inspectors, not third-party firms.

Verbeek concedes that while many third-party inspectors are diligent and honest, some may cut corners.

“It’s like buying a house or hiring a developer or hiring a contractor, you get what you pay for. There are some out there who aren’t as thorough and aren’t as good,” she says.

But Landis says that the responsibility for getting the inspections — and making sure they are completed — ultimately falls on the developer. The problem isn’t the third-party inspection program, but rather developers who try to game it.

“While there may be unscrupulous inspectors, the biggest problem I have heard about is that [inspectors] get fired, that the developer hires them to get started and then actually tells them, ‘I don’t want you to come back to this project, I am not going to pay you to do the close-in inspections and certainly not the final inspections,’” he says.

Bolling says that given the importance of the third-party inspection program and some of the problems that have been revealed with it, she’s planning on making changes to improve it.

“There have been loopholes that have existed that we are closing now so that we won’t continue to have these problems with bad and shoddy construction going forward,” she says.

‘So personal’

Many established developers say that while shoddy and illegal construction does occur, it likely represents a small fraction of all the renovations in the city. But they do concede that even that small percentage can taint the entire industry, and also provoke an outsized reaction due to the emotional attachment that many residents feel for where they live.

“There are bad actors in every industry, and I think because the idea of building someone’s home and their space is so personal and touches people in such an everyday life sort of way, that bad actors in that space have a much more painful effect on people,” says Bo Menkiti, who heads the Menkiti Group, a sales and development group based in Brookland.

Menkiti and other developers and builders say that those actors will always exist in some capacity, and for as much as DCRA can do to stop them, homebuyers can help protect themselves by trying to look beyond the aesthetic elements of renovated homes.

“The most important thing they need to layer on to a good home inspection is to say that they want to see the actual drawings, the drawing sets, and the building permits and the final inspection certificates that were secured before a property should be able to be sold legally,” Landis says.

Finding a good home inspector itself can be a challenge, says Jim Delgado, a former DCRA inspector who retired in 2000 and now does home inspections. That’s because of the close links between some realtors and their home inspectors, who they expect not to delay or derail potential sales.

“There’s a lot of great people out there. But there are a few who know that if ‘I can be the kind of inspector that reports only on the apparent conditions of a house, I don’t upset the cart,’” he says.

“If you as a home inspector take a house apart, you’re deemed a deal killer. If you’re a deal killer, the word gets out, and you’re not going to get referrals. So inspectors walk a very fine line between not getting into legal trouble and not pissing off the realtor,” he adds.

Getting behind the name

An additional challenge for homebuyers can be finding out whom they are buying from. Many developers use limited-liability corporations (LLCs) to purchase and sell homes. It offers them legal protections, but can also mask the true ownership of a property.

Kymber Menkiti, vice-president of sales for the Menkiti Group, says that homebuyers should try to find the name of the person responsible for renovating the property.

“Is there a name? Is it a name you recognize, or is it just a name you can Google and find out information about? A lot of investors are coming in and for their own protection of their business buying it in the name of an LLC, but do you know the name of the person, can you find them, is it an LLC and PO box and they never show up at settlement and you never actually talk to them?” she says.

Landis warns that despite the city’s fast-moving real estate market, it behooves homebuyers to be vigilant early on. “Once they’ve settled, the law is on the developer's’ side,” he says.

No choice but to wait

It’s been more than a year since Crampton filed his lawsuit against Jay Gulati, the Maryland developer he accuses of shoddily and illegally flipping the Columbia Heights rowhouse that Crampton and his wife, Violeta Roman, purchased.

The couple has been out of the house — which after multiple inspections and visits by contractors has been re-gutted — for 18 months. They’re slowly moving towards settlement, though Crampton and Roman are not yet sure what, if anything, they’ll get from the process.

The various residents who purchased from Insun Hofgard are similarly working their way through the legal system. Two filed lawsuits against her, and D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine has been looking into Hofgard and the many homes she flipped.

And while Crampton swings between outrage and frustration over what has happened, he says that he still hopes to move into the house he and his family were so excited about when they purchased it in 2011.

“As soon as we finish the lengthy process of settling the dispute with the house flippers, our goal and our plan is to return the house to a state where we can live in it safely,” he says. “It’ll be a long road, but we do envision ourselves moving back in here and seeing our daughter grow up here as we originally envisioned. That’s what keeps us moving forward.”

Part 2: A Great Fall